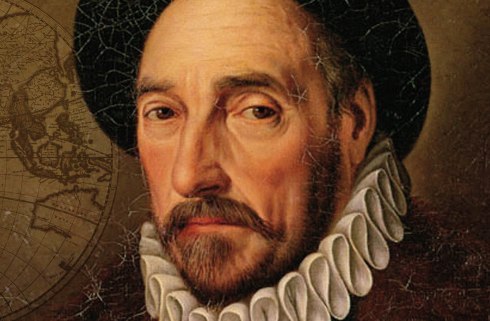

The eloquence that diverts us to itself is unfair to the content

– Montaigne

The essays of Montaigne were first published in 1580, over 400 years old at this point. What I find remarkable is the relevance of his writings even today, and perhaps as a consequence, the many times I have encountered references to Montaigne and his quotes in books not about him. It is as if every aspect of human nature one might contemplate on has already been contemplated in fine detail by Montaigne, annotated with quotes from the ancients. Here are a select few of his quotes from an old edition of his selected essays, with my superfluous commentary

The absurdity of our education is that its goal has been to make us not good or wise, but learned

Montaigne might very well have been tweeting this yesterday. As a thought experiment, if Montaigne was taken seriously, if education really strove to make us wise and good, could humanity have averted the two World Wars and 60+ million deaths? Or put another way, what is the risk of not adopting this bit of important and timeless advise for the future of the world?

It is always a gain to change a bad state for an uncertain one

What Montaigne is saying is that if you are stuck in a rut, and you have a choice where there is a 50% chance of being stuck in a rut vs not, then go with that choice. Except, he says it better

Example is a hazy mirror, reflecting all things in all ways.

If you have wondered how the same incident or story could be interpreted by two people in different ways, here you have it. We observe not just with our eyes, but with our minds.

He who fears he will suffer, already suffers from his fears

Or to quote his fellow Frenchman born 200 years later, Balzac – ‘Our greatest fears lie in anticipation’. I can tell you that just being aware of this maxim works an antidote.

The true mirror of our discourse is the course of our lives

A more familiar version of the above is ‘practice what you preach’, though the Montaigne version sounds so much more profound

Let him be made to understand that to confess the flaw he discovers in his own argument, though it is still unnoticed except by himself, is an act of judgement and sincerity, which are the principal qualities he seeks; that obstinacy and contention are vulgar qualities, most often seen in the meanest souls; that to change his mind and correct himself, to give up the bad side at the height of his ardor, are rare, strong and philosophical qualities

Montaigne is getting borderline judgmental here (meanest?), though he might very well be channeling Nostradamus, divining the collective aspiration of a nation.

The world is swarming with commentaries; of authors there is a great scarcity

Noted.